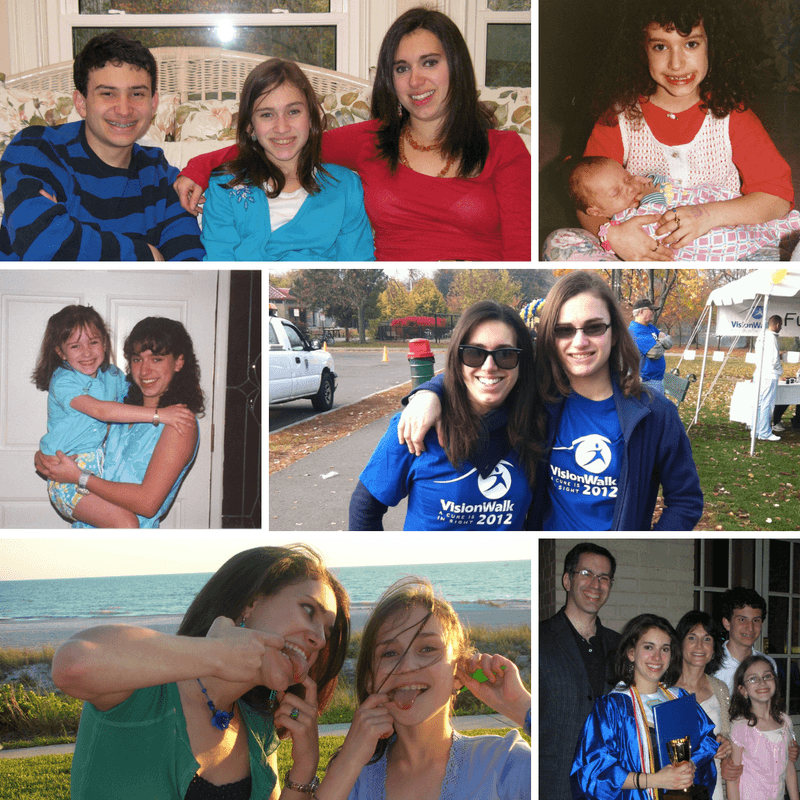

Rachel and Jessica Chaikof face the challenges of losing their vision but are well supported by their parents, Elliot and Melissa, and brother Adam.

Living With Usher 1F - Melissa's Perspective

When our first child was diagnosed as deaf when she was two months old, I cried for 24 hours, and then I needed to do something, and I did. Despite their deafness, my daughters thrived. They successfully navigated their way through mainstream schools and activities thanks to early cochlear implants and Auditory-Verbal therapy. By 2006, with my older daughter finished high school and entering college, I felt that I had earned the right to sit back and relax a bit, that I had climbed that hill and could now sit back and enjoy the view, but that view turned out to be a mountain.

On August 8th, 2006, a date that sticks in my mind, our day started early. My daughters and I had our annual eye exam appointments that morning. At the doctor’s office, my older daughter went into one exam room, and my 11-year-old daughter and I into another. We met back in the waiting room while our eyes were dilating. My older daughter got there first. When I entered, I immediately noticed the anxious look in her eyes. She asked me if anyone had ever mentioned that she had a constricted visual field. I felt my stomach drop, my skin grow clammy, my mind race while trying not to convey my fear to her, but I knew – I knew that this meant the diagnosis we had long feared but thought we’d escaped after years of clean eye exams, the reason my girls were born profoundly deaf –Usher syndrome, the leading cause of inherited deaf-blindness.

We were escorted to another floor, my still oblivious younger daughter skipping along, where we were seated in chairs outside a room and told to wait for the technician, who would perform a visual field test. We waited for over ten minutes, my daughter sobbing, “I can’t lose my vision. I need my vision,” while the technician saw us but ignored us, talking on the phone. I felt helpless. Blindness is a terrifying diagnosis for anyone, but even more so because my daughter was a gifted artist and a month from entering art college. When we’d received the deafness diagnosis, she had been a happy, clueless two-month-old, but now she was 19. Watching her suffer was the most painful thing I have ever experienced. I wanted to fix it, but I didn’t know how. Finally, the department head came out, saw the situation, and ordered the technician to get off her phone and give my daughter the test. Still crying, my daughter had to look into a large sphere and click a button whenever she saw a flash of light.

More tests followed. The day was long and a blur. Our last visit was with the retinal specialist, a visit I can still see and hear in vivid detail today. She had my daughter’s test results, including the printouts of the visual field test. I was sitting there numb and in shock, my daughter still crying, wiping at her eyes, and my younger daughter tired and hungry by then. The doctor held the papers out in front of her, karate chopped them in the middle with her other hand, looked at my daughter with an almost angry look on her face, demanding, “This is severe. It’s not very very severe, but it is severe. How could you not have noticed it!” She then handed us a sheet of paper with information for the low vision center and told us we should go there. That was the end of the appointment. Now I felt anger, perhaps a healthier emotion. How could this doctor be so insensitive? Had she received no training in bedside manner?

At home, my daughter fell to pieces. She got into bed, alternately crying and sleeping, and would not get up for two days, refusing to eat. I needed to focus on helping her through her pain. I couldn’t let her see mine, and so I cried in the shower where no one could hear me. On the evening of the second day, she finally emerged. Seeing her out of bed gave me a sense of hope that we would begin to get through this. And this was a turning point for her. My strong, determined daughter returned, looking up at me saying, “I have never let my disability stop me before, and I’m not letting it stop me now.”

Stay tuned to read the next part of our series, Ten Year Anniversary.